After the frankly horrifying drive across Aberdeen city centre to get to the museum I was definitely in need of a good sitdown. Fortunately for our museum visit the first port of call was the learning room where we got to sit and listen to the learning officer, Lewis Gibbon, and Lynne, a volunteer and ex-drama teacher. The room itself is reasonably big although I doubt they could fit a full class of primary children in at once; Lewis explained that they will take 30 pupils but in three batches of 10 to each workstation.

The first thing we did was to watch an informative and well put together overview of the regiment and the various wars that they have fought in. The video covered conflicts across the British Empire with particular reference to the Napoleonic wars, Afghanistan, and the Boer War. The video was quite dense in parts and consisted of a male narrator with a very slight Scottish accent, interspersed with “memories” from people with a much stronger Doric accent (sometimes with subtitles).

Both Lewis and Lynne were keen to stress that although the museum covers the history of the regiment and therefore includes a lot of material which is violent in nature, the main focus of the educational program in is to explore and get to know the people behind the guns through a mix of primary sources and object-based learning. There was a long table along one edge of the room that had many different objects on it which were part of the handling collection and therefore used to illustrate parts of the workbook issued to schoolchildren. There were also a selection of uniform pieces from various different areas of the regiment, all of which the children are able to put on and dress up with.

We were encouraged to do likewise and it didn’t take long for some of us to work out how to put on various packs, tools, hats, and jackets dotted around the room. Perhaps the most striking thing for me was the size of the uniform jackets, which were absolutely tiny. One of our number struggled to get the jacket to do up, even though he is very slender. We were assured that the jacket in question was not a particularly small one by the standards of the day, but malnutrition and poor healthcare obviously had an effect on the growth potential of the soldiers that were being recruited at this time. Another point that came across through object handling was how heavy the assembled kit would have been (especially for relatively small men to carry). The type of cloth used would almost certainly have become far heavier when wet and as an infantry soldier if there is one thing that can be counted on it is that at some point you will encounter bad weather. We were asked to imagine just how difficult it would be to not only carry such heavy kit, but to fight all day in it, including marching or making a push over the top of the trench.

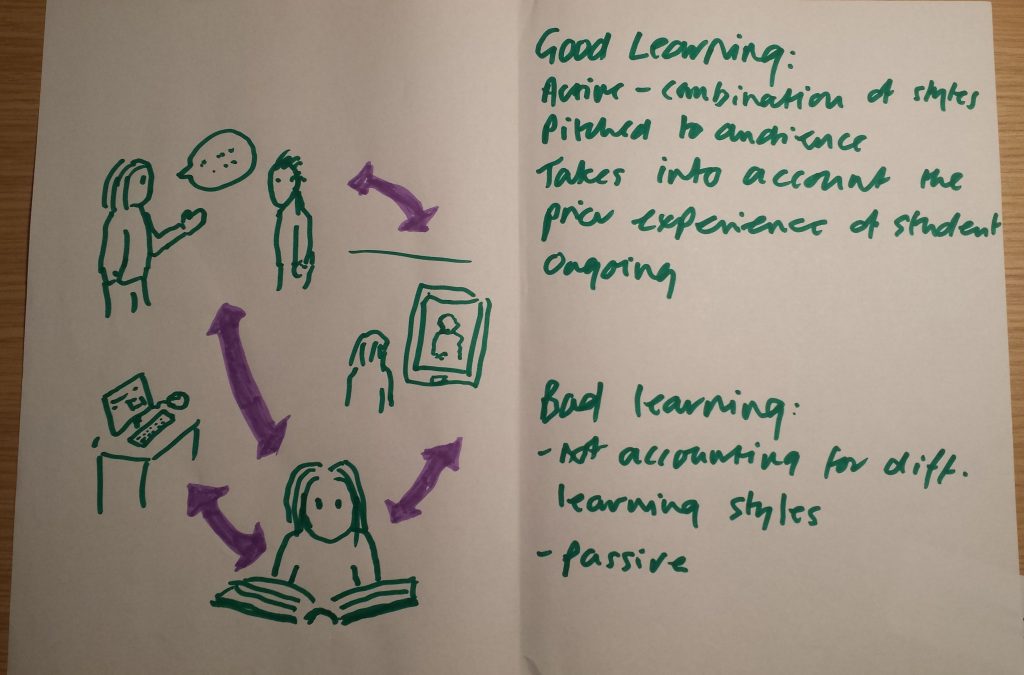

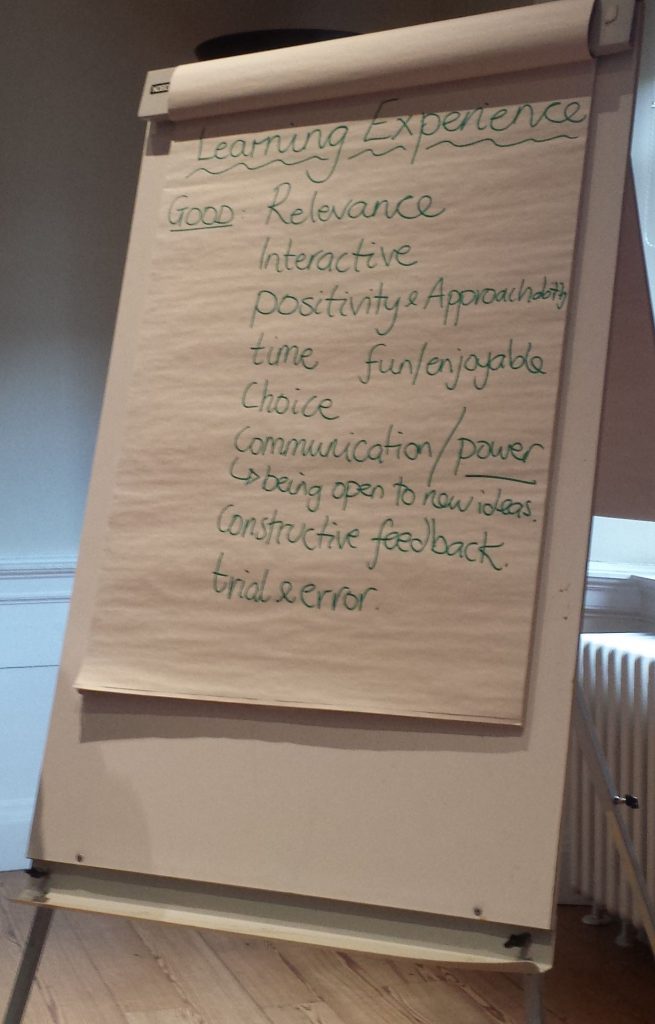

Looking at the workbook provided for primary school children we can see the interactive nature of each workstation having a linked activity consisting of object recognition, reading comprehension, and multisensory/imagination based empathy. There was quite a distinction in the workbook between the question-and-answer section (for example the uniform and equipment questions from workstation one) and the second workstation covering the Battle of Goch, which asked for more from the pupils in terms of relating to an individual soldier; the children were instructed to choose a soldier from the large diorama/model and “place yourself in the soldiers shoes”. The child was prompted to consider what the soldier would have seen by physically aligning themselves with the model to explore sightlines. Likewise they were encouraged to imagine the sounds and smells of battle as experienced by their chosen soldier. This activity changes a static diorama to more interactive and memorable experience for the schoolchild.

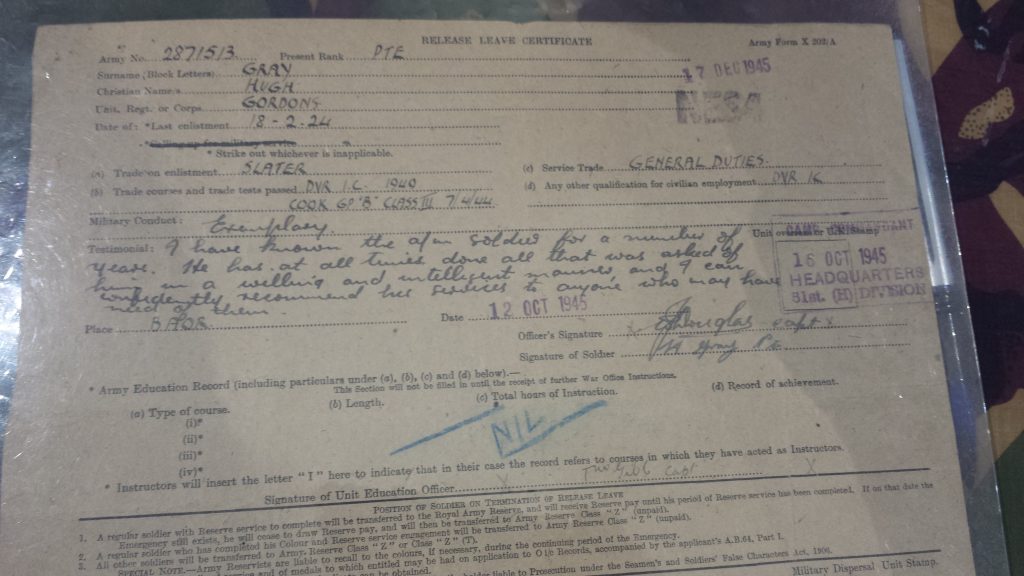

Moving onto another workstation the activity revolved around using primary sources to try and understand the kind of person who would have served in the regiment. The sources included release certificates from the army, pay books, and lists of decorations won in battle. While almost all of these documents were the originals there were measures taken to protect the paper from degradation through both environmental exposure and the deleterious effects of hundreds of sticky fingers by encasing them in clear plastic. This gave children the opportunity to look at the “real thing” without damaging the fragile paperwork.

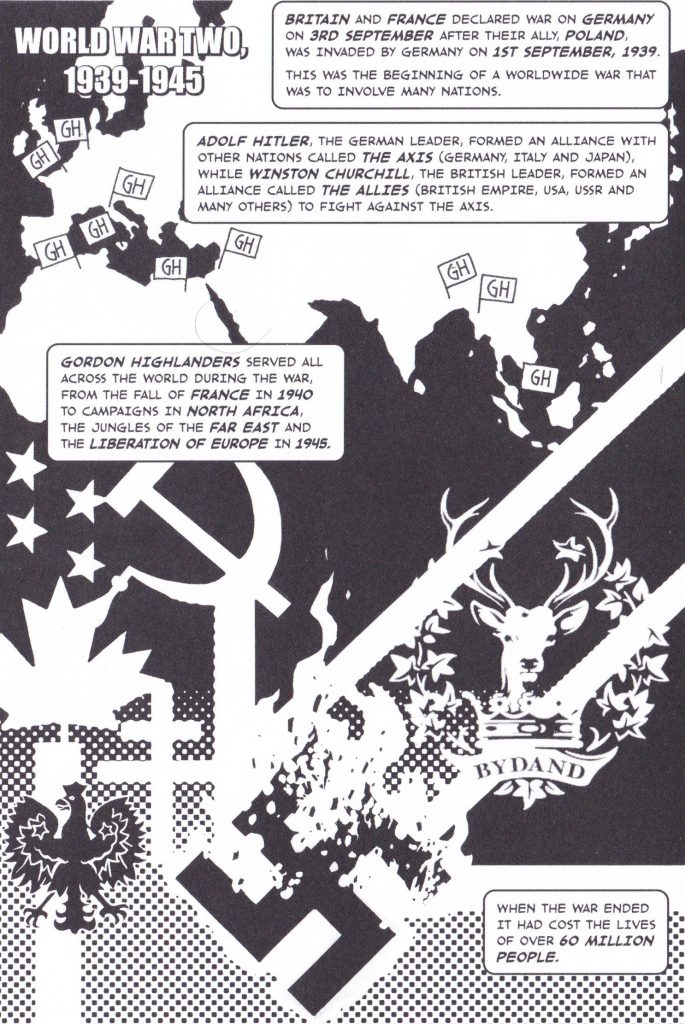

After the talk we had a brief tour around some of the exhibits that related to the Napoleonic wars and the activities of the regiment across the British Empire. For the children the museum provide a comic starring their mascot “Bydandy” the stag and his magical time travelling bagpipes (!). I was interested to see how a comic would deal with the violence and horror of war and noted that the Second World War was handled briefly yet sensitively with an overview panel rather than any gory detail. Throughout the exhibit we walked around there were pull-out sections at child friendly heights and the glass cases included things at an appropriate eye-level for younger children. Most of the text panels were written in an informative and descriptive manner that seemed aimed at the adult visitor who may or may not have any knowledge of warfare.

I think the most interesting part for me (even though I have very little interest in childhood learning/development) was the omnipresent tension between the need to thoroughly present all aspects of the regiment’s history throughout various battles and conflicts of the 19th and 20th century, without in any way glorifying war and violence. I enjoyed this visit and would have liked to have had more time to wander round at my own pace but unfortunately I had somewhere to be immediately after we left. As a delightful denouement to the trip it turned out I had somehow managed to put the steering lock on when I parked my car; releasing said steering lock with one hand almost prompted violence of the scale covered in the various exhibits and certainly resulted in the deployment of several Anglo-Saxon words that would have been familiar to the infantry soldiers of the Gordon Highlanders.